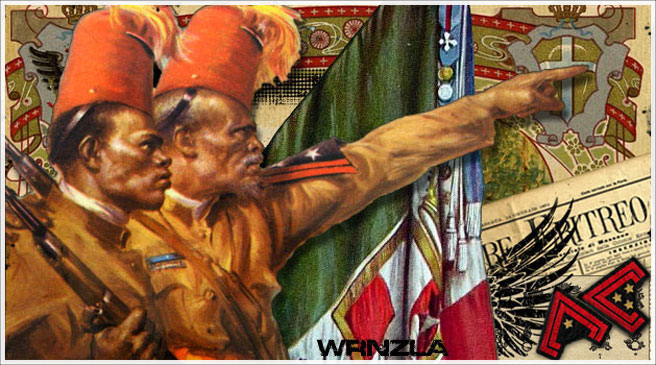

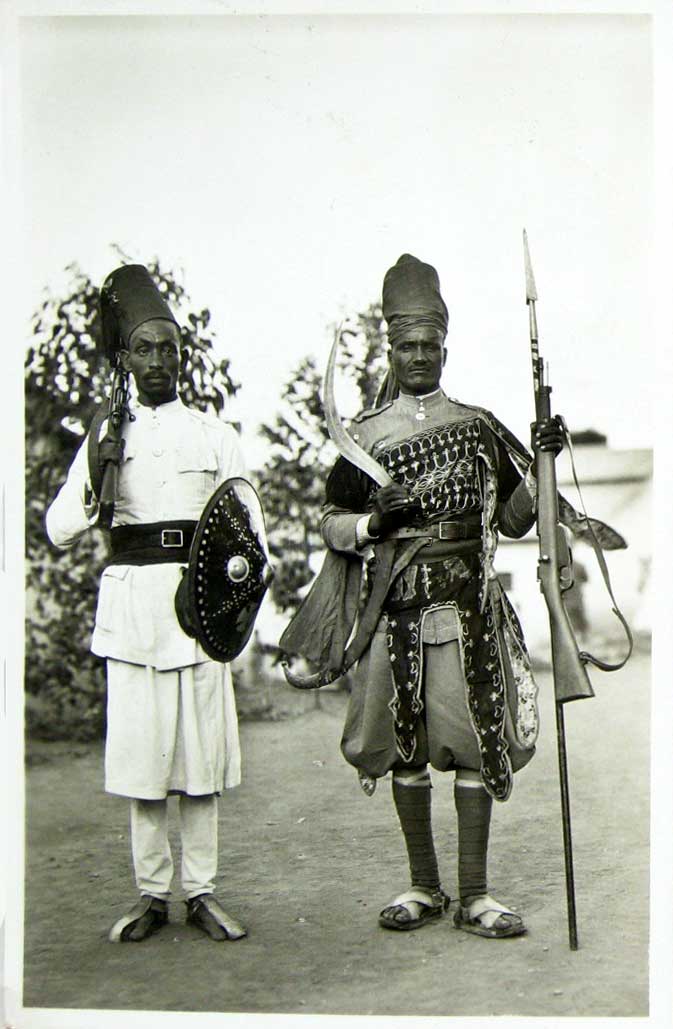

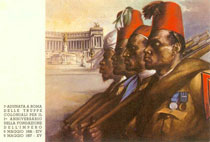

WrnzlaAscari: I Leoni d' Eritrea. Coraggio, Fedeltà, Onore. Tributo al Valore degli Ascari Eritrei. |

L'Ascaro del cimitero d'Asmara.

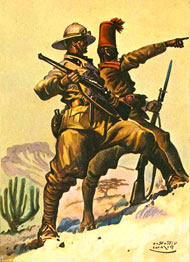

Sessant’anni fa gli avevano dato una divisa kaki, il moschetto ‘91, un tarbush rosso fiammante calcato in testa, tanto poco marziale da sembrare uscito dal magazzino di un trovarobe.

Ha giurato in nome di un’Italia che non esiste più, per un re che è ormai da un pezzo sui libri di storia. Ma non importa: perché la fedeltà è un nodo strano, contorto, indecifrabile. Adesso il vecchio Ghelssechidam è curvato dalla mano del tempo......

Segue >>>

MENU

AREA PERSONALE

TAG CLOUD

ascari ascari eritrei ascari eritrea ascari d'eritrea eritrean ascari eritrea askari eritrean ascari eritrean askari truppe coloniali eritree eritrean colonial troops fanteria eritrea eritrean infantry cavalleria eritrea eritrean cavalry ascari i leoni d'eritrea ascari the lions of eritrea scimbasci muntaz bulucbasci zaptiè

Messaggi di Giugno 2010

|

Post n°375 pubblicato il 25 Giugno 2010 da wrnzla

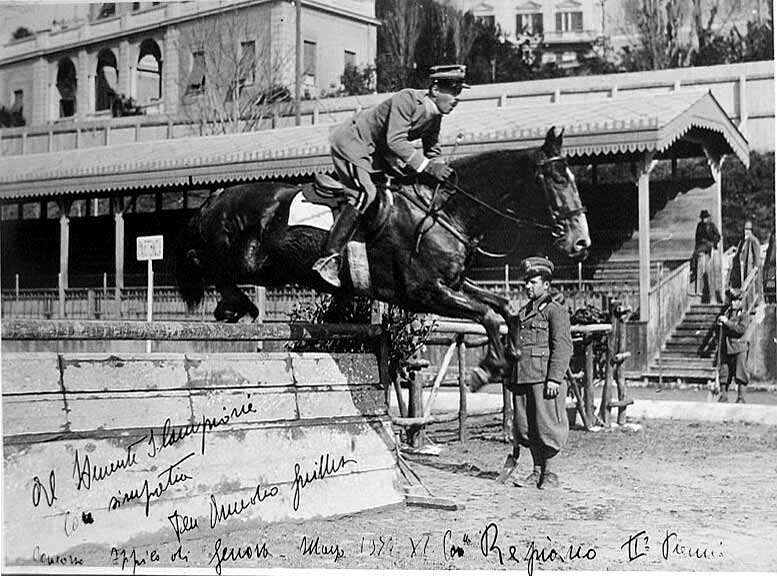

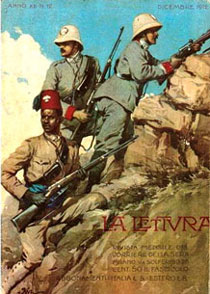

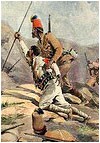

Amedeo Guillet. Piacenza, 7 febbraio 1909 – Roma, 16 giugno 2010 Signor Amedeo Guillet: Refugee and Diplomat in Mutawakkilite Yemen Questioned by Hodeida’s young harbour master, Ahmad Zabara, the limping passenger declared his true identity and his wish to seek refuge in Yemen. But Zabara had to refer the matter to Sana’a, and in the meantime had no choice but to place Amedeo Guillet under arrest. Amedeo was taken to the local prison where a blacksmith fitted iron shackles to his feet. There he languished in conditions of acute privation; and as the days passed and the infection in his wounded ankle spread, he began to wonder whether he would emerge from his prison walls alive. Amedeo Guillet, now in his ninety-ninth year, represents a rare living link withYemen during the rule of ImamsYahya andAhmad. The story of his extraordinary life has been told in vivid and compelling detail by Sebastian O’Kelly (Amedeo: The True Story of an Italian's War in Abyssinia, HarperCollins, 2003 -reviewed on p. 54) It is an epic of adventure, hairbreadth escapes, fearless courage, human endurance and romantic fulfilment. A champion horseman, Amedeo was selected to take part in Italy’s equestrian team in the Berlin Olympics of 1936. Instead, he engineered his transfer to Libya to take part in Italy’s imminent invasion and conquest of Abyssinia. In 1939, he returned to Italian EastAfrica where the newViceroy, the Duke of Aosta, appointed him commander of a 2, 500 strong force known as Gruppo Bande Amhara. To be given this command while still a Lieutenant was a singular mark of the Duke’s confidence. The force, recruited from all parts of Italian East Africa, with Eritrean NCOs and a handful of Italian officers, comprised a core of cavalry with an infantry wing manned mainly by Yemenis. After Italy entered the War on the side of Germany in June 1940, Amedeo’s primary task was to delay the advance of Allied forces into Abyssinia; and in January 1941 at Keru he led a cavalry charge against a column of British tanks – almost the last cavalry charge in the history of modern warfare – which he miraculously survived. But in this and in successive operations in support of Italian forces defending Agordat and the mountain stronghold of Keren, the Gruppo Bande took heavy casualties. With the fall of Keren – the gateway to Asmara – Italian morale suffered an irreparable blow, and in May 1941 the Duke of Aosta, Amedeo’s patron and friend, surrendered to the British. Meanwhile, Amedeo, imbued with a strong ancestral loyalty to King Vittorio Emanuele and Italy’s ruling House of Savoy, decided to fight on. For six months, with the remnants of his now decimated force, he led a guerrilla campaign to disrupt Allied lines of communication. Eventually the net of British intelligence tightened around him; he disbanded his small force, disguised himself as a ‘Libyan Arab’ and went into hiding. With a price on his head, he was saved from exposure by the fierce loyalty of his men to their Commandante, and by the devotion of an Abyssinian girl, Khadija, in whose embraces he had sought solace from the battlefield. Amedeo decided to look for refuge inYemen, and made his way down to Massawa accompanied by aYemeni comrade, Dhaifallah. In late 1941 there were two ways of reachingYemen from Eritrea. One was to obtain a permit from the British port authorities to travel on a passenger dhow sailing once a month to Hodeida. The other was to seek a covert passage in a boat operated by smugglers. Both options required money, and the two men were penniless. So Amedeo went into partnership with a local waterseller. Every day for many weeks he would draw water from a well, load it onto a donkey and hawk it from door to door. In this way he made enough money to pay for him and Dhaifalla to get to Hodeida. Came the day that they boarded a smuggler’s vessel, little expecting to be dumped some hours later on a desert shore miles south of Massawa, and then to be attacked and stripped of all their belongings by Dankali goatherds. Wracked by hunger and thirst, their lives were saved by a passing Sayyid auspiciously named Ibrahim al-Yamani. This lucky encounter with a devout and kindly Muslim enabled them to make their way back to Massawa. In due course, having successfully run the gauntlet of British port security, they embarked for Hodeida with five other Yemeni veterans of the Gruppo Bande . Amedeo’s ordeal in Hodeida’s jail was ended by a message from Sana’a summoning him to the capital. He was now unshackled and treated as an honoured guest. In Sana’a he had meetings with Yemen’s foreign minister, Qadhi Ragheb Bey, a polished diplomat of the old Ottoman school who had remained in Yemen afterTurkish withdrawal from the region in 1919. Amedeo next had an audience with ImamYahya who declared himself a friend of Italy and promised Amedeo a house and salary. To an extent, Amedeo was the beneficiary of Italy’s assiduous courtship ofYemen in recent years; a courtship which had resulted in a bilateral treaty of economic cooperation, the delivery to Yemen of military hardware and the establishment in Sana’a of an Italian Medical Mission (where Amedeo had his infected ankle successfully treated by the much respected Dr Luigi Merucci). Given his problematic relations with the British in Aden, the Imam had no qualms about welcoming a man who had eluded their attempts to kill or capture him in Eritrea. In return, Amedeo made himself as useful as circumstances permitted: he trained the Imam’s bodyguard and, drawing on his veterinary knowledge, succeeded in containing an outbreak of fly-borne cattle sickness in Marib. Crown Prince Ahmad expressed interest in meeting the Arabic-speaking former Italian cavalry officer, and Amedeo’s visit to him inTaiz foreshadowed the close relationship which he was to establish with ImamAhmad when he returned toYemen as a diplomat in the 1950s. In mid-1943 news reached Amedeo of British plans to repatriate Italian civilians and wounded servicemen from Eritrea, in the Red Cross ship Giulio Cesare. With some difficulty he obtained ImamYahya’s permission to leaveYemen for Massawa with the aim of smuggling himself on board. He accomplished this in the guise of a native coolie, and, with the connivance of the ship’s Italian captain, stowed away until the British guards left the ship at Gibraltar. Amedeo married his fiancée, Beatrice Gandolfo, in 1944, and after the end of the war and the abolition of the Italian monarchy, he resigned his military commission (by now he held the rank of Colonel) and entered the Italian Diplomatic Service. His first posting was to Cairo in 1950. A few years later, when Yemen began to open diplomatic relations with the outside world, he was transferred toTaiz. ImamYahya had been assassinated in 1948, andAhmad, hisson, was now ruler. Amedeo and his wife travelled by air to Aden, driving overland to Taiz, a journey which then took all of eleven hours. Ahmad was visibly pleased to welcome back his old friend, ‘Ahmad Abdullah’, and in the years that followed he would rely on Amedeo’s advice more than that of any other Westerner. Under Amedeo’s aegis numerousYemeni students and pilots were sent to Italy for study, and the Imam’s visits to Rome for medical treatment reflected his trust in Amedeo’s arrangements there for his welfare. Beatrice Guillet looked back on their time inYemen as the most magical period of her life. The Guillets sent their two sons Paolo (born in 1945) and Alfredo, three years younger, to an Italian boarding school in Asmara which in the 1950s still had a sizeable Italian population. The boys spent their holidays inYemen, escorted on expeditions outside Taiz by the faithful Dhaifallah whom Amedeo had re-employed at the Italian Legation. Amedeo was able on occasion to use his influence with the Imam to assist his Western colleagues, and became a close friend of the British Charge d’Affaires in Taiz, Christopher Pirie-Gordon, who spoke fluent Italian. Margaret Luce, wife of Sir William Luce, Governor of Aden (1956–60), recorded the following in her account of their visit to Taiz in 1959, published in her book From Aden to the Gulf: Personal Diaries 1956–1966 (Michael Russell, 1987): ‘We went out to lunch with Dr and Signora Guillet . . . He is Italian Charge d’Affaires here, in spite of his French-sounding name, an ex-cavalry officer, and rather alegendary character. When the Duke of Aosta was defeated in Eritrea in the war, [Amedeo] Guillet led a final resistance against us so successfully that we put a price of £3, 000 on his head. He urges Christopher Pirie-Gordon to try and collect this now, and share it with him . . . He is small and spare and dynamic, a passionate horseman, and a passionate royalist. . . Horses and music are his two great loves, and he refuses to be sent anywhere by his Foreign Office where he can’t keep horses and ride . . . He is a very great personal friend of the Imam and has known him for eighteen years. When the Imam was so ill this year and taken to Rome, Dr Guillet was with him the whole time. The Imam thought that perhaps he was dying, as in fact he nearly was, and the one person he always wanted and asked for was [Amedeo] Guillet, who never failed him, even in the middle of the night. He is very fond of the Imam, and says that he has the greatest admiration for the immense will-power with which he conquered both his illness and his addiction to morphia, and came back and took a grip again on his country . . . The Guillets’ house was given to [Amedeo] by the Imam . . . It is a completely Arab house in the middle of the town . . . and surrounded by Yemeni families and their children . . . [Signora Guillet] is rather young, and gentle and sweet, with red hair. . . She has made the house as charming as it could be, and filled every little rooftop and open space with tubs of geraniums and poinsettias and hibiscus . . . ’ One of Imam Ahmad’s farewell gifts to Amedeo when he left Yemen in June 1962, on transfer as ambassador to Jordan, was a handsome Hamdani colt. Amedeo called the horse Nasr and it accompanied him to Jordan and later to Morocco when he was posted there as ambassador. Nasr’s grandson, Akbar, kept at Amedeo’s country house in Ireland, remained alive until 2006. In September 1962, Imam Ahmad died and was succeeded by his son, alBadr. Amedeo travelled from Amman to Sana’a to represent the Italian President at the funeral, and was lodged in the Maqam palace. The night of the funeral he was awoken by the sound of cannon fire. Tanks had begun to bombard the palace in an Egyptian-backed coup against the new Imam. AlBadr and a few followers, half-dressed and loading their weapons, burst past Amedeo and made their escape through the window of his room, jumping down into the garden below. Many of Amedeo’s closest Yemeni friends were murdered in the days that followed. By an odd quirk of fate, Amedeo was en poste in Morocco when King Hassan was the target of an assassination attempt. Amedeo last visited Yemen in 1991 as the official guest of the government, and since then has relied on his sons, Alfredo and Paolo, to maintain the Guillet family’s link with the country. In 1975, following his final diplomatic appointment as Italian ambassador in Delhi (where his equestrian skills were much in demand), Amedeo and his wife retired to the Georgian Rectory which they had bought in Co. Meath, Ireland. Today Amedeo, now a widower, divides his time between homes in Rome and Ireland . . . wa la hawl wa la quwa illa billah! The main source for this article has been Sebastian O’Kelly’s biography of Amedeo Guillet. The Editor gratefully acknowled ges the author’s assistance, and the permission kindly given by Ambassador Guillet for photographs from his collection to be published with the article. |

|

Post n°374 pubblicato il 24 Giugno 2010 da wrnzla

Lutto per l'Italia: è morto Amedeo Guillet, eroe d'Africa . Il Barone Amedeo Guillet, ufficiale di cavalleria, ambasciatore, agente segreto, ma, soprattutto eroe d’altri tempi, è morto mercoledì scorso, 16 giugno nella sua abitazione romana. Il 26 giugno prossimo, nella Cattedrale di Capua, alla presenza dell’Arcivesco di Capua, Monsignor Bruno Schettini, e della massime autorità civili e militari, con inizio alle ore 17.00, saranno accolte le ceneri dell’Eroe per essere deposte nella Cappella di famiglia presso il cimitero di Capua. La notizia, per la maggior parte degli italiani e degli stessi cittadini di Capua, di cui era “cittadino onorario”, sembra quella di una normale news di carattere funerario, ma non è assolutamente così.

Articolo di: Nunzio De Pinto da Napoli.com ----------------------------- Il Blog è partecipe al dolore per la scomparsa del Il Barone Amedeo Guillet, ufficiale di cavalleria e ambasciatore, porgendo le proprie più sentite condolianze ai famigliari, amici, semplici conoscenti ed a tutti coloro che di qualsiasi razza, fede politica e religione lo hanno ammirato ed amato. Addio Amedeo Guillet. Wrnzla. ----------------------------- Links interni: |

|

Post n°373 pubblicato il 23 Giugno 2010 da wrnzla

Un'Italia senza memoria storica Articolo tratto da: www.ordinefuturo.info Per puro caso sono venuto a conoscenza nell’anno 2010, a 85 anni di età, dell’ennesima ingiustizia fatta dall’Italia nei confronti di combattenti che, in un passato lontano, ebbero il coraggio di servire con eroico coraggio una Madre Patria, oggi matrigna e volutamente smemorata. |

|

Post n°372 pubblicato il 15 Giugno 2010 da wrnzla

|

|

Post n°371 pubblicato il 15 Giugno 2010 da wrnzla

|

INFO

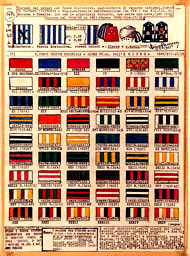

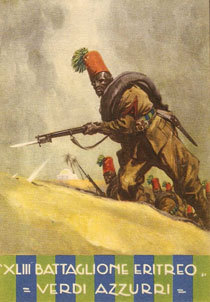

- Due Medaglie d'Oro al Valor Militare alla bandiera al corpo Truppe Indigene d'Eritrea.

- Due Medaglie d'Oro al Valor Militare al gagliardetto dei IV Battaglione Eritreo Toselli.

Medaglia d'oro al Valor Militare alla Memoria.

Medaglia d'oro al Valor Militare alla Memoria.

QUESTA ╚ LA MIA STORIA

.... Racconterà di un tempo.... forse per pochi anni, forse per pochi mesi o pochi giorni, fosse stato anche per pochi istanti in cui noi, italiani ed eritrei, fummo fratelli. .....perchè CORAGGIO, FEDELTA' e ONORE più dei legami di sangue affratellano.....

Segue >>>

CERCA IN QUESTO BLOG

A DETTA DEGLI ASCARI....

...Dunque tu vuoi essere ascari, o figlio, ed io ti dico che tutto, per l'ascari, è lo Zabet, l'ufficiale.

Lo zabet inglese sa il coraggio e la giustizia, non disturba le donne e ti tratta come un cavallo.

Lo zabet turco sa il coraggio, non sa la giustizia, disturba le donne e ti tratta come un somaro.

Lo zabet egiziano non sa il coraggio e neppure la giustizia, disturba le donne e ti tratta come un capretto da macello.

Lo zabet italiano sa il coraggio e la giustizia, qualche volta disturba le donne e ti tratta come un uomo...."

(da Ascari K7 - Paolo Caccia Dominioni)

DISCLAIMER

You are prohibited from posting, transmitting, linking or utilize in any other form the contents relevant to the WRNZLA/BLOG/WEBSITE for offensive purposes including, but is not limited to, sexual comments, jokes or images, racial slurs, gender-specific comments, or any comments, jokes or images that would offend someone on the basis of his or her race, color, religion, sex, age, national origin or ancestry, physical or mental disability, veteran status, as well as any other category protected by local, state, national or international law or regulation.